By Lysa Legros

Staff Writer

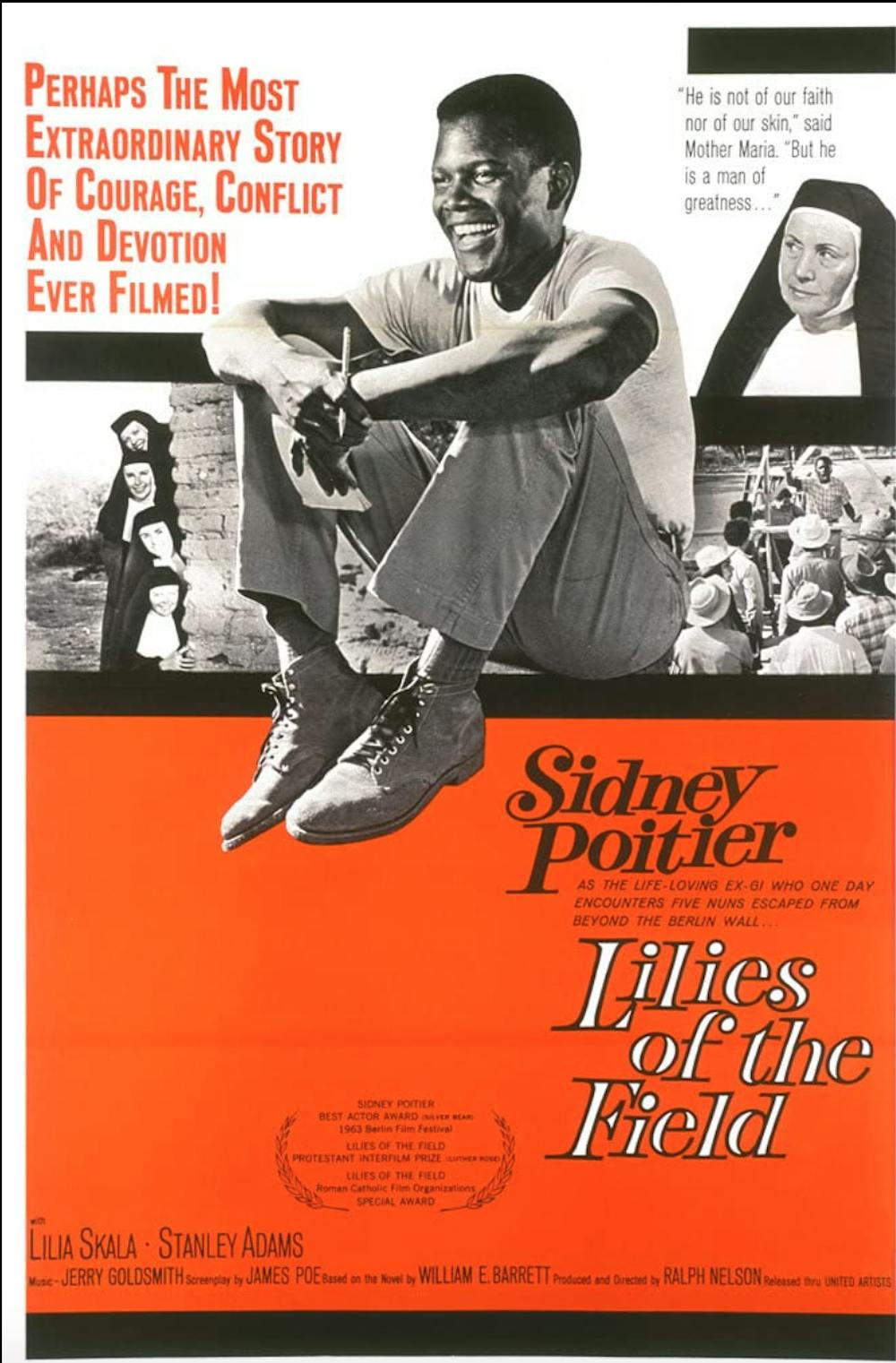

Sidney Poitier was a distinguished actor, director, diplomat and author. He was the first African American to win an Oscar for Best Actor (“Lilies of the Field”) and was an actor who redefined what the Black male lead could look like. Poitier’s characters, much like the man himself, were dignified, honorable and courageous. They were meaningful because they showed that the elevated male lead was not an archetype that only white men could play. Yet, as awe-inspiring as Poitier’s characters were, they pale in comparison to the integrity, determination and bravery of the man himself.

Poitier, 94, passed away in his home in Los Angeles on Jan. 6. However, his legacy lives on.

From the beginning of his life, the odds were set against him. Poitier was born on Feb. 20, 1927, two and a half months premature to Bahamian parents on vacation in Miami. However, within three months, young Poitier recovered his strength and the family returned to the Bahamas.

As an adolescent, Poitier was often reckless and mischievous, so when he was 15, his father arranged for him to live with their relatives in Florida, hoping that the new environment would help him settle down. Poitier could not adjust to the racism of Florida and left on his own to New York, where he had no relatives or connections.

In New York, he supported himself as a dishwasher. One day, while scanning a newspaper for dishwashing jobs, he found an advertisement from the American Negro Theater group requesting actors. Curious about the job, he auditioned for the program. However, his accent and his poor reading ability caused the interview to go disastrously, and the interviewer kicked him out of the building. His parting remarks forever changed the course of Poitier’s life.

“He said, ‘Stop wasting people’s time. Why don’t you go out and get yourself a job as a dishwasher or something?’” Poitier said in his interview with the Academy Class of 2014. Upset by the man’s remarks, concerned about how he had discerned that Poitier was a dishwasher and scared that he was fated to always be a dishwasher, Poitier resolved that he would become an actor to prove to him wrong.

From that point onwards, he doggedly pursued acting. After learning that the American Negro Theater had an academy, he auditioned to join the program but was rejected. Crest-fallen but determined to receive acting lessons, he returned to the school, and asked if he could join in exchange for doing janitorial work and the director acquiesced to his request.

As a student of the American Negro Theater Academy, Poitier understudied in “Days of Our Youth” for Harry Belafonte, the principal actor. One night, Belafonte could not attend the show, so Poitier filled in for him. That night, a visiting Broadway director came to view the show, and he was so impressed by Poitier’s performance that he invited him to audition for his upcoming play, “Lysistrata.” Although his part was small, Poitier was extremely nervous because the audience was much larger than that of the Negro Theater Academy and he mixed up his lines.

Dejected from that first experience, he left the theater with the intention of quitting acting.

“Truth is, I left the theater thinking to myself, ‘That’s it. I tried; I don’t have the gift,” Poitier said. Then, the next morning he saw the morning paper. “Lysistrata” was met with raving reviews, and so was he. Emboldened by his performance’s positive reception, Poitier decided to continue acting. A Broadway producer in the audience enjoyed Poitier’s performance so much that he requested for him to join his tour production of “Anna Lucasta.”

In the 1950s, when Poitier did make it to the big screen, he made a name for himself by playing upstanding and composed characters in films that explored the racial tensions between white and Black Americans, and the desire for a unified unprejudiced, unsegregated America. In 1950, Poitier made his screen acting debut in “No Way Out,” where he played a doctor who was hired to heal two racist white murder suspects. He took on a variety of roles in the early ‘50s, but it was in the mid-‘50s, that he became widely known. In 1955, he secured his breakout role in “Blackboard Jungle” where he played a rebellious and astute student who attended an interracial urban high school.

In 1958, he was nominated for an Oscar for best actor alongside Tony Curtis in “The Defiant Ones,” a film about a pair of black and white inmates who are shackled together and run away together. In 1959, he acted in “Porgy and Bess,” alongside Dorothy Dandridge. In 1961, he starred in the film adaptation of “A Raisin in the Sun.” In 1964, he won the Oscar for Best Actor for “Lilies of the Field.”1967 was a busy year for him, filled with career highlights such as “In the Heat of the Night,” “Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner” and “To Sir, with Love.”

“In The Heat of the Night” was particularly memorable because of a scene where Poitier’s character, a detective, was slapped by a racist white police chief, and he slapped him back. The scene resonated with black people all over the world because it spoke to their inner dignity in a world of subjugation. The scene almost didn’t exist.

“The scene required me to stand there, this guy walks over to me, and he slaps me in the face, and I look at him fiercely and walk away. I said, ‘you can't do that … The black community will look at that and say that is egregious. You can't do that because the human responses that would be natural in that circumstances are suppressed to serve values of greed on the part of Hollywood and acquiescence on the part of people culturally who would accept that as the proper approach.’ I said, ‘you can't do it,’” Poitier said.

The director adjusted the scene according to Poitier’s demands.

At the end of the 1960s, Poitier took a break from acting and returned to the Bahamas. He returned in the 1970s as a comedy director. In 1972, he acted alongside Harry Belafonte and starred in “Buck and Preacher,” a self-directed film. Throughout the 1970s, he directed and made appearances in films such as “A Warm December” (1973), “Uptown Saturday Night” (1974), “Let’s Do it Again” (1975), and “A Piece of the Action” (1977). In 1980, he directed the wildly successful “Stir Crazy,” starring Gene Wilder and Richard Pryor, and in 1982, followed it up with “Hanky Panky,” starring Gene Wilder and Gilda Radner.

He made fewer film appearances in the 1980s and broke his hiatus from the industry in 1988 with the action thriller “Shoot to Kill” and the action-comedy “Little Nikita.” In the ‘90s, he took on a variety of acting roles, some of the most notable being Thurgood Marshall in “Separate but Equal” (1991), and Nelson Mandela in “Mandela and Der Klerk” (1992). His final acting role was “The Last Brickmaker in America,” a somber yet uplifting drama that explores themes of grief and fatherhood.

In the 2000s, Poitier published “The Measure of A Man: A Spiritual Autobiography” and won a Grammy for best spoken word album for the audiobook version of the memoir. In 2008, he published “Life Beyond Measure: Letters to my Great-Granddaughter,” a set of letters that reflect upon and offer insights about his life.

He was a non-resident Bahamian ambassador to Japan from 1997 to 2007 and to UNESCO (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization) from 2002 to 2007.

Some of his honors include being appointed a Knight Commander of the British Empire in 1974, being awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2009 and receiving a Chaplin Lifetime Achievement Award in 2011.

“Hope is the eternal tool in the survival kit for mankind. We hope for a little luck. We hope for a better tomorrow,” Poitier wrote in his book, “Life Beyond Measure: Letters to my Great-Granddaughter,” reminding all of us to move forward in spite of seemingly impossible odds. “We hope, although it is an impossible hope, to somehow get out of this world alive. And if we can't and don't, then it is enough to rejoice in our short time here and to remember how much we loved the view.”