By Tristan Weisenbach

Editor-in-Chief

The College is in a financial crisis. At least, that’s what many people on campus are calling it. Some administration officials may be hesitant to say it publicly, but the bottom line is that we’re struggling.

The College was sitting on just over $360 million in debt as of the end of the fiscal year that ended in June 2023, according to S&P Global Ratings, a leading global credit rating agency.

S&P revised its outlook on the College’s financial stability from stable to negative, citing continued budgetary pressure throughout the following two fiscal years and “the college's modest level of financial resources in comparison to total debt outstanding and total adjusted operating expenses.”

Students, faculty and staff are feeling the constraints of such a grim budget outlook. Class offerings are being reduced while class sizes increase. Some building maintenance is being deferred until it’s absolutely necessary. Academic departments are being restructured to prevent academic funding cuts, and department budgets are being downsized — all to save every dollar possible.

President Michael Bernstein was brought to the College nearly two years ago as the 17th president, tasked with solving this financial burden. His administration has been working tirelessly to do the most with the least, developing working groups aimed at solving specific issues on a thin budget, and identifying new revenue sources wherever possible.

However, operating on less means working with less, and the campus community is feeling the struggle. How can state legislators expect an administration to be fully committed to academic excellence when it also needs to prevent itself from going bankrupt? Our administration is certainly doing its best, but it doesn’t have to be this way.

The state of New Jersey has neglected the College for years now, denying it the funding that it rightfully deserves as the No. 1 College in the North region, as ranked by U.S. News & World Report. Year after year, the College gets pennies of an increase — if at all — compared to other colleges and universities across the state.

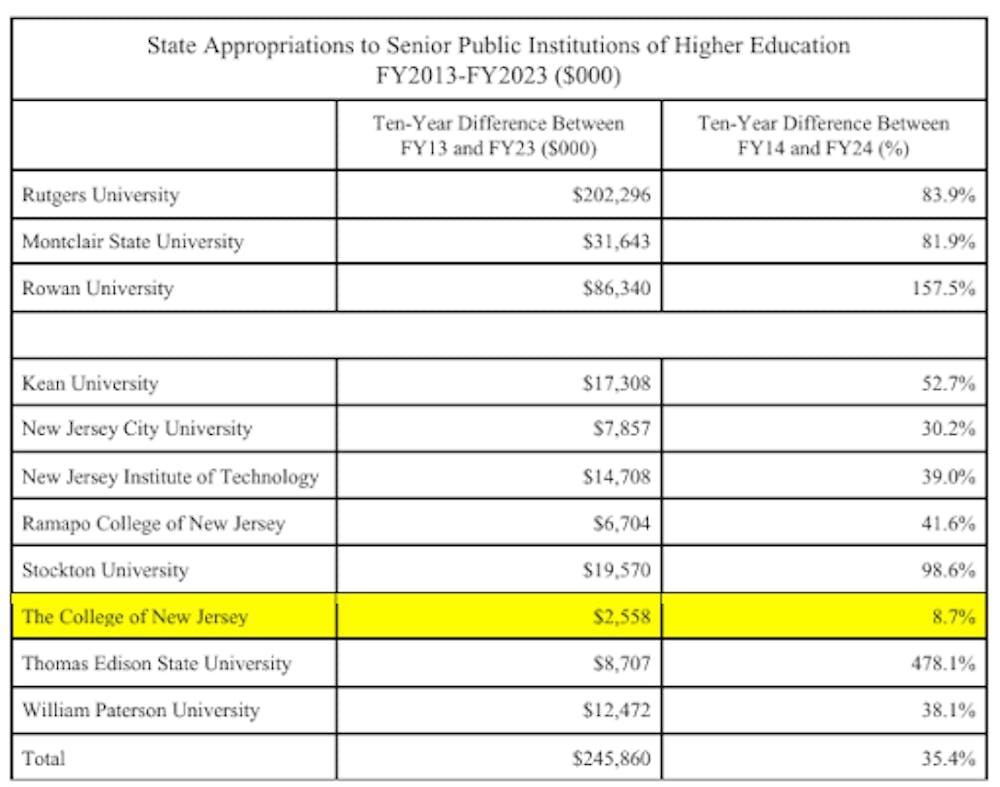

From fiscal year 2014 to fiscal year 2024, the state of New Jersey provided millions of dollars in additional funding to many other schools, according to New Jersey state appropriations budgets. Rutgers University, for example, saw an 83.9% increase in its funding from 2014 to 2024. Rowan University, a 157.5% increase. And Thomas Edison State University saw the largest difference in funding, a 478.1% increase. Where does the College sit on this list?

The College received the lowest 10-year state appropriations increase compared to all other public institutions in New Jersey. (Graph provided by Jennifer Keyes-Maloney)

All the way at the bottom, with just an 8.7% increase over the last 10 years. That’s right. 8.7%. The only school to see a single-digit percent increase.

What’s the story behind our lack of state funding? How did we get here?

How the state budget process works

The State of New Jersey’s budgeting process is a multi-month long procedure that starts in February. The governor of the state announces their budget proposal before handing it over to the state legislature to work out the details.

The current governor, Phil Murphy, announced his budget proposal on Feb. 25, and he is proposing a cut in funding to many higher education institutions across the state, including the College.

State funding in New Jersey has different components. The general appropriations that the College receives are broken into two categories: general allocation and outcomes based allocation.

This fiscal year, the College received just over $28.5 million in general allocations, and just under $6 million in outcomes based allocations, according to the state budget. Outcomes based allocations are determined in a formulaic way and take into consideration criteria such as the number of degrees granted, the number of low-income students, the number of transfer students and more.

For fiscal year 2026, the state has recommended providing the same amount of money for the general allocation, but reducing the outcomes based allocation by nearly $2 million. Combined, the state is recommending a total base operating funding allocation of about $32.5 million.

However, the College requested a little over $84 million for this current 2025 fiscal year, according to a copy of its state funding request — a much greater amount than what was ultimately allocated.

Impacts on students

Students are feeling the effects of the state refusing to increase our allocations year after year after year.

Just one example is the increasing number of students per class, slowly chipping away at one of the College’s proudest selling points — small class sizes — because it can’t sustain them financially.

According to the College’s Quick Facts webpage, the average number of students per class is 23. However, a previous version of this webpage from 2021 listed the average class size as 21 students.

As student journalists, we feel these struggles in our classes too, along with many of our friends. If New Jersey state legislators hear these issues and still continue to decline increases in appropriations, they cannot label themselves as true supporters of higher education.

With higher allocations, the College could expand its course offerings, providing students with more opportunities to delve into various research sectors, explore different areas of interest and gain expertise in more niche disciplines within their majors.

Impacts on faculty

With expanded course offerings comes an increased need for faculty and staff, too.

Bernstein implemented a temporary hiring freeze soon after he began his term just under two years ago in an effort to reduce the College’s budget deficit. While there have been exceptions for filling positions that are essential, most other positions remained unfilled for quite some time. Some have yet to be rehired.

When the College hires faculty and staff, it must support those employees with benefits like healthcare, in addition to their salaries.

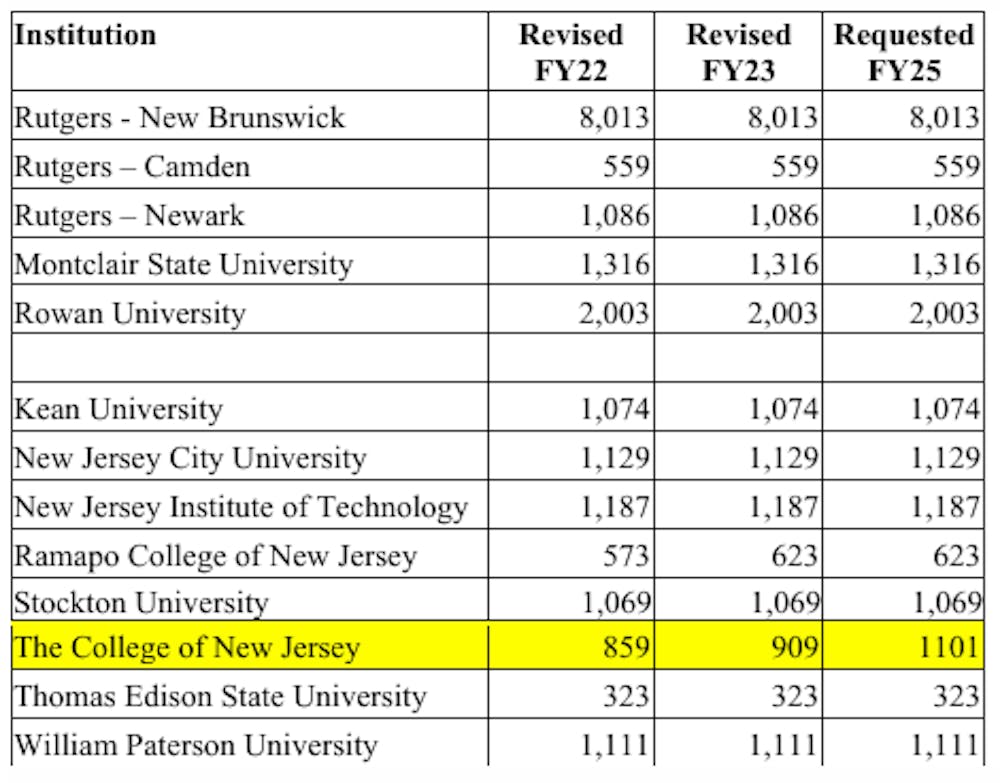

The state offers support for this in the form of fringe benefits. Currently, the College is approved for state funding for fringe benefits of 909 employees, according to state appropriations data. However, the College is requesting that number to be increased to 1,101 employees, according to its state funding request.

The College is requesting the state to provide fringe benefits for the additional 200 employees that it has failed to recognize in past fiscal years. (Graph provided by Jennifer Keyes-Maloney)

Since the College is a public institution, employees who work here are state employees. The College has to reimburse the state for the fringe benefits of employees that are not covered under the annual budget. This comes out to about 200 employees that the state has declined to recognize with fringe benefit support that the College must reimburse the state for — a total estimated cost of around $9 million annually.

State legislators are not proponents of higher education if they refuse to recognize all employees who work to provide students with an elevated educational experience. State legislators are not proponents of providing state employees with fair workplace benefits if they leave it up to an institution in financial turmoil to carry the burden of funding them, despite the state having the resources to do it.

Impacts on facilities

Class offerings and employee benefits only account for part of a college’s expenses. The facilities that students live and learn in are equally as important.

There are many academic buildings that provide students with state-of-the-art tools and spaces to thrive in. The Art & Interactive Multimedia building is fit with a Makerspace, painting and recording studios, and an art gallery. The Science Complex houses a multitude of labs with new, revolutionary equipment that spurs advanced research projects.

However, the College’s dorms are notorious for being in need of a little sprucing up, particularly Travers and Wolfe Halls, known as the Towers. These 10-story brick buildings were built in 1971, and in recent years have been plagued with numerous maintenance issues.

Some first-year students who live in them cite their nostalgic elements, and enjoy the bonding opportunities that they provide. However, the lack of air conditioning, malfunctioning elevators and crumbling infrastructure cannot be overlooked much longer.

At the start of the fall 2023 semester, a particularly hot September month sent multiple students living in the Towers and other residence halls to the hospital suffering from heat-related illnesses due to the lack of air conditioning. This past fall, multiple elevator burnouts caused problems for students, oftentimes triggering fire alarms, resulting in the entire building being evacuated.

Proposals to address the Towers date back to at least 2015, when plans were drawn up to knock down the Towers and replace them with low-rise residential buildings. However, that plan was scrapped due to the cost, according to a memo sent to the campus community by former President Kathryn Foster in February 2022.

Two years later, another plan was floated to renovate Travers and Wolfe Halls one at a time, but that, too, turned out to be too costly, and the plan was ultimately scrapped, according to the memo.

Most recently, in 2022, Foster’s memo announced a plan that the Towers would be slowly phased out while new village-style residential housing was constructed on the outskirts of campus, with an anticipated closure date for the Towers by the fall 2024 semester. However, this plan, too, did not see the light of day because of its cost.

The Signal has learned that this plan would have likely cost the College approximately $120 million to complete — a hefty price for an institution already facing hundreds of millions of dollars of debt.

Last year, The Signal obtained a copy of a request-for-proposal from fall 2023, shortly after Bernstein began his tenure, in which the College was once again seeking out a way to replace the Towers. The RFP stated that “TCNJ has an urgent need to close its existing Travers and Wolfe Halls (‘TW’) due to the age and condition of the facilities.”

The College was seeking a public-private partnership with a company that would ultimately construct the replacement housing along the outskirts of campus, replacing the 1,050 beds that the Towers have with 500-800 beds in the new development.

However, this plan presented some issues. By forming a public-private partnership, the College would lose future room and board revenue from students, which would go to the private company rather than the College. Also, the reduction in the number of beds would mean on-campus housing would become more competitive for students to obtain.

The connection between the two towers, known as “the link,” also houses numerous underground connections for integral campus-wide infrastructure systems, such as HVAC, steam and water. Because of this, any demolishment of the Towers would need to take extra precautions to preserve these systems.

The Signal later found out that replacement was not the only possible solution being considered at the time though, and that the College was also investigating the potential to renovate Travers and Wolfe Halls, or other possible plans that have not been disclosed. However, to this day, no formal plans have been announced about how the College will address the looming issue of the Towers.

First-year housing is one of the most decisive factors that influence where a student chooses to attend college. The most recently constructed student housing, Campus Town, is a public-private partnership that was opened in 2015 and features apartment-style living for mostly upperclassmen. However, living in Campus Town is technically considered off-campus, since the College does not operate these dorms or collect room and board revenue from them.

Many of the residence halls that are open to first-year students were built decades ago. While some have undergone renovations in more recent years, they are still quite outdated when compared to newer dorm buildings like Phelps and Hausdoerffer Halls, both of which opened in 2009.

If a student is comparing two similar schools in terms of academics, but one has newly-built, air conditioned dorms and the other has decades-old, un-air conditioned dorms, which school do you think that student will choose?

This is especially true now that the College is implementing a first-year residential requirement for the upcoming fall 2025 semester. All first-year students, with a few exceptions, will now be required to live on-campus — many of which will live in dorms with no air conditioning, plagued with an ever-growing list of maintenance issues.

The College’s current financial situation prevents it from obtaining the funding needed to construct new residence halls or renovate existing ones. If the College thought $120 million was too much to renovate or replace the Towers a few years ago, think about how much it’s going to cost now, in the midst of rising inflation, tariffs and economic uncertainty.

The College desperately needs the state’s help in securing funding to address Travers and Wolfe Halls, along with other capital projects. New Jersey has done it before, and it can do it again. In 2021, the state allocated $400 million to improving higher education infrastructure across the state, according to the New Jersey Monitor. Now is not the time to wait around.

In the past, various bond and grant authorities in the state have issued funding for capital projects at the College, including $40 million through the Building Our Future Bond for the STEM Building that was completed in 2017, and $33 million through the Office of the Secretary of Higher Education of New Jersey in 2023 for renovations to Forcina Hall and Roscoe West Hall, as well as network upgrades and academic equipment.

This fiscal year, the College asked for $25 million in support from the state for expanding its business program to accommodate increasing undergraduate and graduate enrollment in the School of Business. The project would “provide additional workforce training programming, create innovation/incubator space, and house the Small Business Development Center under the same roof.” Its request for funding this year was not met.

Deferred maintenance is another area that the College is requesting support for. The College has been working on emergency repairs on its underground steam heating system for multiple years, costing upwards of $14 million, according to its state funding request. Much of the underground infrastructure is about 90 years old, well beyond its typical lifespan and in desperate need of replacement. This project would cost about $32 million total — a cost that the College requested support from the state for this fiscal year. The College also asked for $9.7 million for upgrades to its fire safety system.

Where we go from here

The looming financial crisis that the College is dealing with is not entirely the state’s fault. But, it’s not inherently the College’s own fault, either. Could the College have managed its deferred debt from past bond agreements better? Yes. Could the College have cut smaller costs wherever possible sooner? Yes.

But the state could have done more a long time ago, too. If it had stepped in and increased its allocations in years prior, the College would not be in the situation it’s in right now. And the College has been lobbying state legislators for years, working tirelessly to spread awareness about our need for increased funding, only for those calls for help to fall on seemingly deaf ears.

U.S. News & World Report just ranked New Jersey as the No. 1 state for education. Despite this, more than half of New Jersey high school graduates attend college out of state — about 30,000 students per year, according to mycentraljersey.com.

Pennsylvania, on the other hand, has a majority of its high school graduates stay in-state for college. Plus, it’s also one of the top three states that students from out of state go to for college. One of the most common states that these students come from is New Jersey, according to WHYY.

If state legislators want to stop letting Pennsylvania and other states steal its college students, then they need to start paying more attention to what the real needs of its in-state colleges and universities are, and start investing in them. Abandoning the College, its best performing public higher education institution, to drown in debt is not the way to build a reputation of a state that supports higher education.

State legislators: it’s time to band together and provide The College of New Jersey with the allocation funding that it rightfully deserves. Don’t continue to abandon our institution’s hard-working students, faculty, staff and administrators any longer.