By Ashley Ragone

News Editor

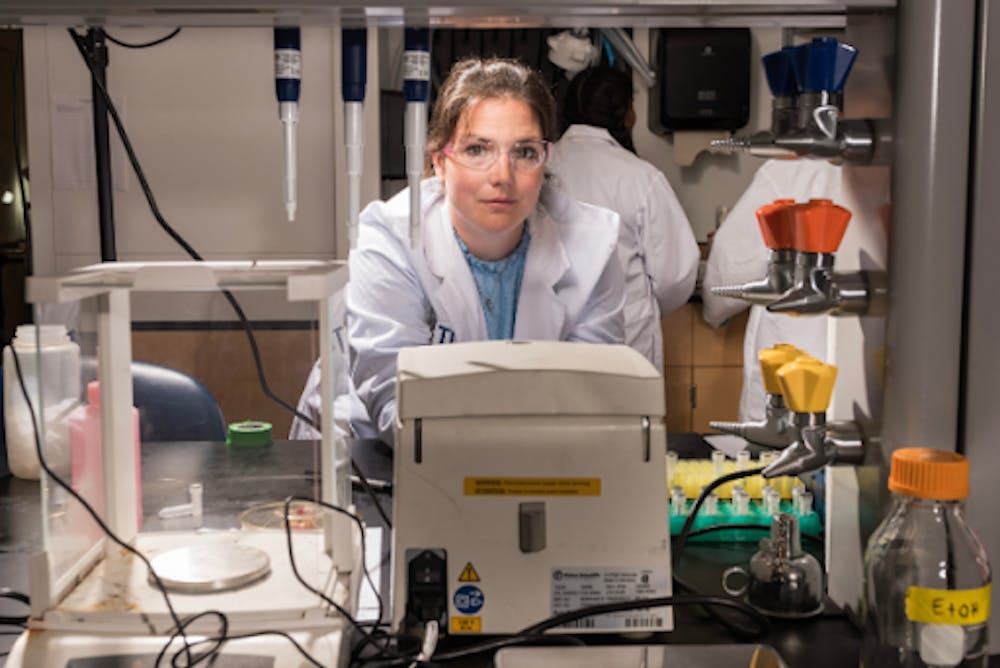

Alexis Mraz has been chosen to receive the Gitenstein-Hart Sabbatical Prize for the 2026-27 year, sponsoring her research into Legionella and its persistent habitation in water.

Mraz, who is both an associate professor of public health and affiliated within the environmental studies department, will take a sabbatical year to further study the bacteria, and aim to reduce the morbidity and mortality of the associated Legionnaires’ disease.

The prize, which was created by the College’s former President R. Barbara Gitenstein and her husband Don Hart, recognizes and supports a faculty member taking a year-long sabbatical for scholarly work. The prize is awarded based on the research’s overall merit and potential contribution to its wider field, including the educational benefits students of the College may receive, according to the prize’s website.

Legionella, a bacteria known to thrive in warm water ecosystems, is an opportunistic pathogen that is most common in the plumbing of hospitals and hotels.

Mraz will be continuing her long-standing work with the bacteria, a bug that she finds to be an ideal long-term case study, as it won’t be going away anytime soon.

“My dissertation focuses on Legionella and it really came out of, at the time, regular Legionellosis outbreaks, specifically Legionnaires’ and specifically in hospitals and large apartment buildings in this area,” she said.

Legionellosis, the name for any disease caused by the bacteria, and Legionnaires’, a lung infection spread through water droplets, are both prevalent within communities and individuals already vulnerable; this includes those already sick, the immunocompromised and the elderly.

“You have this bacteria that’s really ubiquitous, so it’s present in a lot of different places, but it’s really challenging to treat. It’s opportunistic, so it’s not making everybody sick, but the people who it is making sick, it tends to make them really sick,” Mraz said.

Part of Mraz’s research examines how water quality in community distribution systems affects the concentration of the Legionella bacteria. Common sources include travel-associated infections from hotel premise plumbing, community-acquired infections from poorly maintained cooling towers, or aerosolized bacteria in a hospital setting. She noted how problematic this infection could be, as patients on contaminated ventilator systems can be left with bacteria buried deep in their lungs.

Particularly worrisome is the high case fatality rate of the disease.

“The case fatality rate in the general population is about 10%,” Mraz said. “To put that in perspective, COVID-19, during the beginning, was about 1.8%. But the case fatality rate when we’re looking at hospital-associated infections is closer to 25%, and sometimes has been recorded as high as 40%.”

In the Northeast U.S., the older status of water distribution systems and high biofilm build-up also contributes to the high rates of Legionellosis incidents. A 2015 outbreak in New York City resulted in 138 diagnoses and 16 deaths from one Bronx cooling tower alone, and New Jersey health data reports hundreds of new cases every year.

Mraz’s research efforts, however, have faced a share of obstacles. Recently, she lost funding that resulted in her inability to complete data analysis and risk assessment.

“I was working on an [Environmental Protection Agency] grant where we collected a lot of data throughout the country,” she said. “So we had a whole lot of data about Legionella concentration, different disinfected byproduct concentrations, and other water quality parameters, but that grant was canceled by the [Department of Government Efficiency].”

Mraz shared that the reason given for the sudden cancellation was that “it was no longer a national priority.”

With growing tensions and issues in funding surrounding DEI–based work in the federal government, Mraz could not find any logical explanation for her grant’s elimination. “We thought we might get through because the work really had nothing outlined that was, you know, ‘woke.’ It wasn’t focused on minority groups, or women, or even impoverished people. I don’t know,” she said.

“There were four of these grants that were funded at the same time with the same goal, to reduce morbidity from opportunistic pathogens…but all four of them were cancelled. We got the notice, and like two weeks later, there was another incident in the Bronx, where I think like 14 people died,” Mraz said.

Mraz hopes that her research in this coming sabbatical will at least answer some questions in the field of microbiology and allow for further improvements in the maintenance and treatment of Legionella.

“The overarching, ideal end-goal is that we’re reducing morbidity and mortality from Legionella. I mean, obviously, that's lofty, right?” Mraz said. “But really, the first thing I'm trying to figure out is how Legionnella is working within the biofilm…it’s like a protein matrix that's built out by all the different microbes that are going to end up living in the [plumbing system].”

Mraz recognizes she may not realistically solve the issue of Legionella growth in water sources, but her goal is to understand the bacteria’s ability to thrive within plumbing based on the water quality. This information would provide a useful framework to further tackle the future elimination of Legionella entirely.

“I think the goal has to be how can we control it in a way that’s effective in not getting people sick,” she said.

Following her return from the 2026–27 sabbatical, Mraz is expected to present a collegewide lecture based on her research’s findings, according to the Gitenstein-Hart website.